In our last issue you learned what a story is, and WHY stories are so powerful.

I also introduced the notion of stories being “constructed” or “built”, rather than written in an open ended way.

There are, as we’ll discover, many story structures that have been developed to help screenwriters produce hit movies.

But today, we’ll talk about the one story structure that, in my mind, is the most important of them all, and the one most of the other story frameworks used in Hollywood got their inspiration from.

I’m talking about the somewhat famous “Hero’s Journey”.

But before doing a deep dive into Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey, let’s stop for a minute to answer some questions that I know some readers will have in mind while reading these lines:

“Why should I be interested in story structures used for full-feature films?”

“We can only make really short videos with AI, so all this theory is pointless!”

Of course, you’d be completely –and painfully– wrong!

For several reasons:

First, story structure applies to films –and not only to films– of any length.

A good story is a fractal!

You need a solid story structure for a 120-minute feature, and you also need it for a 10-minute short.

Actually, since story is a fractal, you need a solid structure not only for the full story, but also for the skeleton of every sequence and every scene in the story!

The second mistake many people wanting to become AI filmmakers make is due to their lack of understanding of the pace of AI progress…

As someone who has done some technical research in the field of AI since 2017, and still struggles every day to keep myself acceptably up to date with the new models and breakthroughs happening almost daily, I can attest to the fact that the the field is moving at neck-breaking speed.

And this speed of research is compounding every single day, with dozens of frontier AI research labs from all over the world fiercely competing to one-up each other.

AI Video is no different.

If anything, it’s one of the areas of GenAI that’s getting the most attention –and capital allocation– this year, so many of the things that might remain an issue with AI video models, as of now, won’t be for long.

Every time we face an industry in rapid development, especially if that development seems to be exponential in nature, we cannot make the mistake of preparing for today’s capabilities.

It’s imperative that we make the counterintuitive effort of looking past current capabilities, and prepare for what Sam Altman calls: “the adjacent possible”.

The “adjacent possible” is everything that’s not possible yet, but that will become possible in the next few months.

Yes, I’m talking months here.

AI’s rate of improvement is exponential in nature, and at that rate, no many problems remain unsolved for more than a few months!

I consider this to be a must-have mindset if you’re expecting to make a career in any field related to AI.

But what does that mean in the context of AI Filmmaking?

Once again, you need to look at the adjacent possible: full-feature films created entirely leveraging video generation models are just around the corner.

Moreover: I dare to say we’ll see the first full-feature film created entirely using AI –not by AI– before the end of the year.

But here’s the thing:

ANYBODY can now create a video clip, a short movie, and pretty soon a feature film using AI image and video platforms!

This is being made more and more easy, cheap, and accessible every passing day.

You know what one thing not many people will be able to pull off?

Create a GOOD MOVIE!

Because creating a good movie has nothing to do with what AI models you’re using, or how advanced the technology has gotten or will get…

Creating a good movie is, and has always been, about how good a storyteller you are!

Notice that I didn’t say “how good a story is”, since a great storyteller can make the most mundane story feel magical!

So now that you understand why we are dedicating time to properly study story structure, let’s go back to the Hero’s Journey.

If you remember, I touched on Joseph Campbell and his book “The Hero with a Thousand Faces” in last week’s issue of this newsletter.

I also explained there that was Chris Vogler who famously introduced Campbell’s discoveries and ideas to Hollywood in a memo he wrote when working as a story consultant for Disney in the 80’s.

Years later, Vogler presented his simplified version of the Hero’s Journey in his book “The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers”.

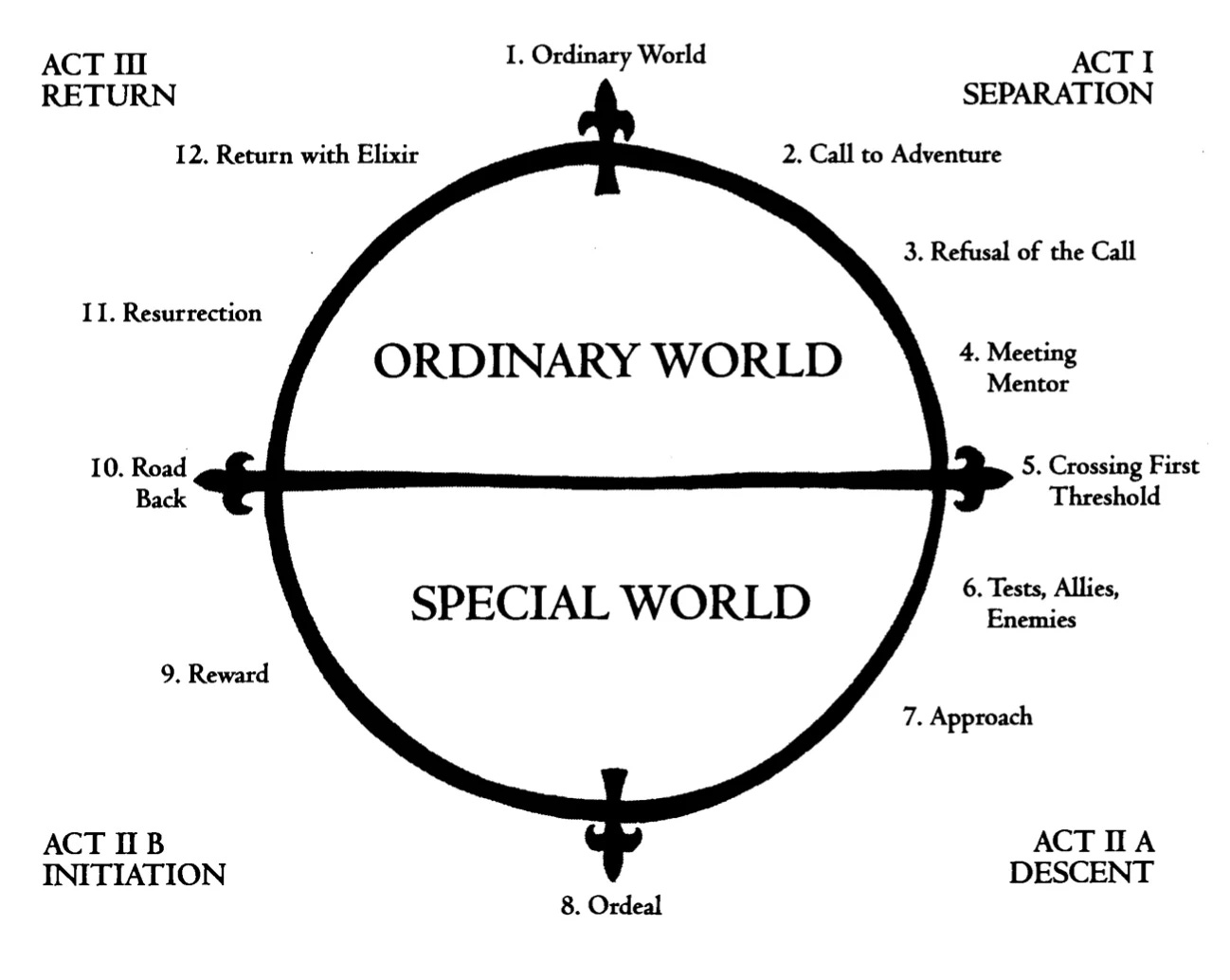

Vogler’s simplified version –down from Campbell’s 17 stages to only 12 stages– merges some of the original stages and subtly redefines others to make the framework more practical and useful for his specific audience: screenwriters.

Today, Vogler’s simplified version is the one that’s more frequently used by screenwriters who want to follow the Hero’s Journey.

But in order to understand why the Hero’s Journey is so useful as a story structure, we first need to know what big problem it solves for writers and, especially, screenwriters.

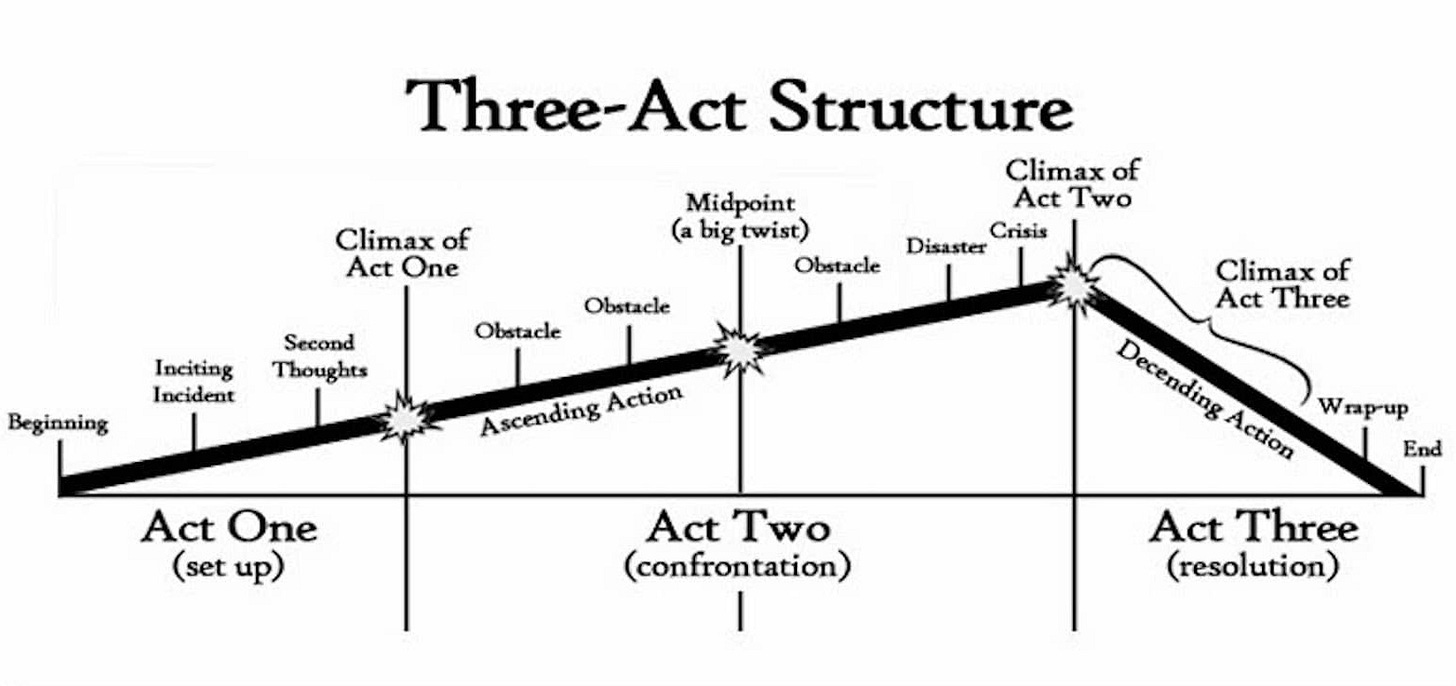

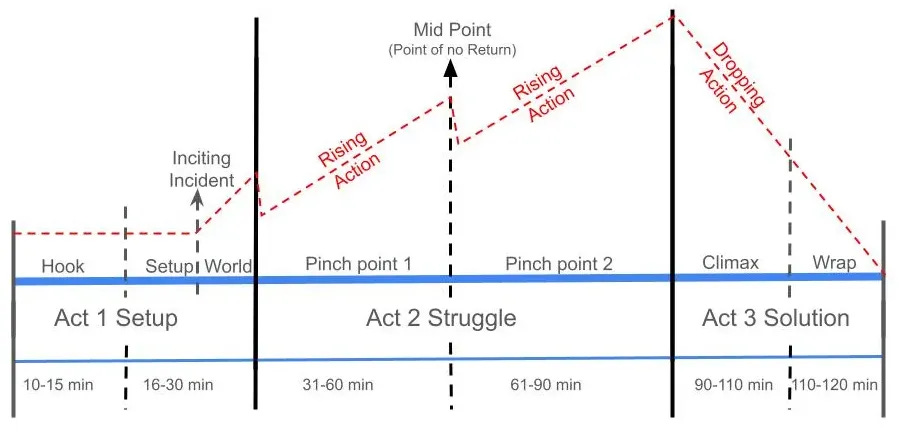

And for that, let me introduce you to the most iconic story structure every play and movie has been based on since the times of the ancient Greeks: The 3-Act Story Structure.

In its more basic, original form, the 3-Act Structure is pretty simple:

Act 1 — Setup

Act 2 — Confrontation

Act 3 — Resolution

As you can see, this hardly gives us any more information than what we already know: that a story must have a beginning, a midpoint, and an end.

Of course, this feels like a little too broad to serve as guidance in the writing process, so in time many more detailed variations appeared in the screenwriting community.

Here are the 2 variations presented by StudioBinder in their article on the 3-Act Structure In Film:

As you can see, the first image at least gives us a good idea of the emotional arc and action ramp-up we need to go for in each Act, while the second image is much more prescriptive in regard to what to include, and at what specific times.

There are many other renditions of this 3-Act Structure, some of which even give us the specific timing at which each major event –or beat– should happen on screen, sometimes down to the minute!

But whatever rendition of the 3-Act Structure you want to follow, you’ll always end up facing the same problem:

How are you supposed to fill the 60 pages of Act 2?

Act 2 is, as you can see by the graphs above, double the size of Act 1 and Act 3, and there is no clear orientation as to what to include, other than a series of obstacles and rising stakes, as we saw last week.

Act 2 is split in half by the midpoint, which is the most important beat in the entire story, creating two distinct sections that are commonly known as “Act 2-A” and Act 2-B”.

Some screenwriters think this is nonsense and simply divide a movie into Four Acts, instead of the classic Three.

Now, this is the point where a lot of writers get a little uncomfortable…

Many writers tend to think that following a proven story structure will make their stories predictable and less original.

This cannot be further from the truth.

If it were true, then all stories we have ever read and watched would look and feel the same, since as Campbell discovered, all stories ever told in the history of human civilization have followed the exact same signposts!

But there is another really important reason why you should embrace story structure in your writing:

Art never comes out of a blank canvas of infinite possibilities; real masterpieces always emerge from constraints, and the unique ways in which the artist masterfully works within and around those constraints!

It might sound counterintuitive, but constraints breed creativity, not the other way around!

The worst thing that can happen to a writer, their worst nightmare, is sitting there, staring at a blank page!

The worst thing that can happen to a screenwriter is to go blank wondering what should happen in the play, and in what order, for the story to work!

This is a problem that, as you can see, the 3-Act Structure is ill-prepared to solve.

That’s why I decided to focus on the Hero’s Journey as our first stop for understanding story structure.

In future newsletters, we’ll study other story frameworks widely used by Hollywood screenwriters, such as Blake Snyder’s Save The Cat (SAT), Michael Hauge’s Six-Stage Plot Structure, and Dan Harmon’s Story Circle.

But as you’ll see, most of these screenwriting frameworks have been inspired directly or indirectly by The Hero’s Journey, so I feel it’s really important for you to be somewhat familiar with the original, even if later on you decide to use a different story framework.

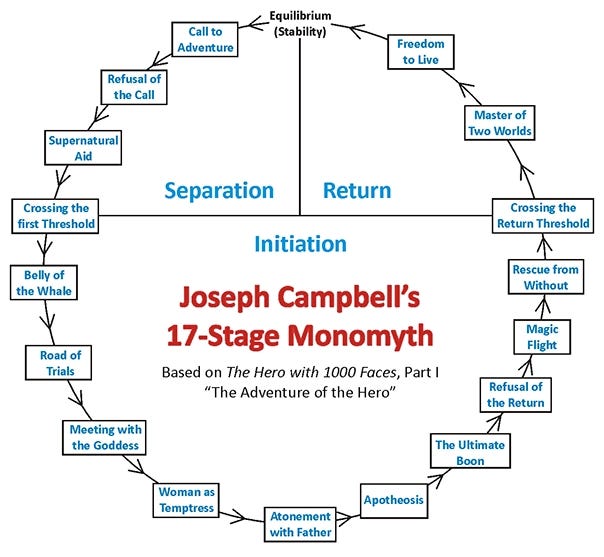

The original Hero’s Journey as presented by Campbell in his 1949 book has 17 Stages, describing a full circle:

The first thing to remember is HOW Joseph Campbell came about these distinct 17 phases in the Hero’s Journey, also known as “the Monomyth”.

He wasn’t a screenwriter, or a novel writer; he was a mythologist who spent his entire career studying ancient cultures, mythology and comparative religions.

After analyzing all kinds of religious stories, cosmologies, and traditions from all over the world and spanning thousands of years, Campbell found that all these stories were, in fact, one and the same story.

He called this “master story” the Hero’s Journey because it always tells the story of a reluctant hero who receives a Call To Adventure and symbolically descends to the underworld –or Special World– where he needs to go through a Road of Trials in order to experience a profound TRANSFORMATION –Death & Resurrection– to conquer the Elixir and become Master of Two Worlds.

The 17 Stages of the Hero’s Journey map incredibly well to all the legends of mythological Gods, Titans, and Heroes present in all ancient cultures, and also describe with impressive accuracy the lives of Prophets and Messiahs as narrated in the sacred books of all major religions.

Not surprisingly, this story structure seems to be intimately connected with us at an unconscious, almost instinctive level.

That’s why stories that follow this millenary structure feel so attractive and satisfying to us, in a way that we cannot explain.

Many blockbuster Hollywood movies follow this story framework to the T Star Wars is a classic example, as George Lucas was a fan of Campbell’s work, but there are many, many more.

Next week, I’ll be using my favorite movie –The Matrix– to show you how this story framework works in practice!

The first thing I want you to notice looking at the diagram of the Monomyth above, is how Campbell uses a circle to describe the Journey, instead of a chronological left-to-right line as we saw in the 3-Act Structure.

This circle closes on itself, implying a Return to the starting point, which is a key concept in the Monomyth.

The second thing I want to bring to your attention is how this circle is divided into 3 regions, called Separation, Initiation, and Return.

The Initiation region is by far the biggest region –bigger than the other 2 regions combined– since this is the Special World where all the TRANSFORMATION happens in the Journey.

This region is equivalent to Act 2, the longest Act in the 3-Act Structure, the part where the meat and potatoes of the story happen.

Notice that, in contrast to the 3-Act Structure, the Monomyth informs us in great detail of what should happen in Act 2!

I think this is a good moment to clarify that if you want to use The Hero’s Journey as a guide to write your script, you should consider these 17 stages as an orientation rather than a prescription.

Not all stages have to necessarily appear in your plot, and if they do, they might appear in a slightly different order.

Also, sometimes certain stages might be embodied in the arc of a secondary character instead of the hero’s, like we’ll see when we analyze “The Matrix” next week.

The first quadrant of the Journey, equivalent to Act I, is called Separation because the protagonist –the Hero of the story– must let go of his Ordinary World in order to start the Journey of Transformation that happens in the Initiation quadrant.

Separating these 2 quadrants is the First Threshold, a point that in other story frameworks is sometimes called “The Point Of No Return”, simply because here’s where the protagonist finally commits to the Journey –either willingly or compelled by circumstances out of his control– to the point that going back to the Ordinary World becomes impossible.

On the right side, coinciding with Act 3, we see the third region or quadrant called Return.

The hero must go back to the point where the journey started, the Ordinary World, but now having experienced a full TRANSFORMATION that made them Master of Both Worlds.

This Journey, as you can clearly see, has a deep and rich psychological meaning: that “new world” the hero is thrown into and which he must master through the trials of Initiation is no other than his inner world!

This, right here, is the main difference between Campbell’s Hero’s Journey and Chris Vogler’s Writer’s Journey.

Campbell's work is primarily a work of comparative mythology, aiming for a broad psychological and cultural analysis of universal patterns in human consciousness and storytelling.

His stages often carry deep symbolic and psychoanalytic weight.

Vogler's adaptation, however, is geared towards pragmatic application in narrative construction, particularly for screenwriters.

Vogler’s steps are framed as a toolkit for structuring compelling and emotionally resonant stories, focusing on plot points and character functions that drive the narrative forward.

As I explained in our last issue, a story is always about a character going through a process of TRANSFORMATION.

When the main character, the protagonist, successfully goes through that transformation, that symbolic Death & Resurrection in the Hero’s Journey, he becomes the Hero he’s been called to be.

Notice that, while the entire journey is called “The Hero’s Journey”, the main character only becomes a Hero if he (or she) prevails at the end.

Consequently, it would be more accurate to think about the journey as “The Journey To Become A Hero”, rather than a journey taken by someone who already is a hero!

This is the perfect moment to address the debate that’s been going on for ages among writers and storytellers:

Should we start with the Plot, or should we start with Character development?

In creative writing, in case you’re not aware, there are 2 schools of thought:

Some writers like to write the skeleton of the story first, the plot, defining all the events that will happen in the story, and the order these events will happen in.

Once the full story is more or less scripted, they go on to design the characters that will better fit that story.

The other school of thought is that of writers who prefer starting with character development: they thoroughly design multi-layered, complex characters first, including their backstories, their desires and wants, their wounds, and their internal and external motivations and conflicts.

Once the writer understands the characters completely, they simply let the characters react naturally to the events in the plot, in full accordance with their own personalities, motivations, and weaknesses.

Which one of these approaches do you think will end up with better stories?

There are excellent writers in both camps so, as always, the best approach is the approach that works for you.

That said, for me, there is only one answer that makes sense:

Always start with the characters, and especially, with the main character: the protagonist, the Hero.

When you start with the plot, the characters usually end up feeling flat, with no real psychological depth.

They appear to have been an afterthought for the writer, and, most importantly, the actions they take in the story do not always make sense.

Sometimes it feels as if the character did something just because the writer needed it to happen, not because this is obviously the way this character would react to such a situation due to their particular motivations and flaws.

When this happens, the illusion is broken.

The reader, or the spectator, is taken aback; they might not know exactly why, but the immersion is gone and they might find it difficult –or plainly impossible– to reconnect with the story!

Contrarily, when the writer deeply knows each character’s motivations, strengths, and flaws, and the particular way the character sees the world –which sometimes is referred to as “the character’s lie”– the story grows organically out of each character’s actions!

The writer, knowing exactly how the hero and the other characters would react to every event in the plot, simply lets the story tell itself!

Which takes us to my last argument for always starting with character development:

This is how stories are created in real life!

The story of our lives is written not by the events that happen to us, but rather by the reactions we have and the decisions we make when confronted by these events!

These reactions and decisions are forged in our inner world by our own particular way of seeing the world, our moral codes, and our character’s flaws.

In the last issue, I told you that a story is always SOMEONE’s STORY.

It’s always SOMEONE’s Journey of Transformation.

A Hero’s Journey.

There is no journey without a hero, and no story without a WHO.

That’s why the WHO always goes first.

I rest my case.

I’ll see you next week for a full analysis of “The Matrix” using the original Joseph Campbell’s 17 stages of the Hero’s Journey!

Until then,

Leonardo

P. S. Loving Flawlessly Human?

Please take a couple of minutes to support my work by sharing it with your friends and colleagues:

You can also share this particular issue using the button below:

THANK YOU IN ADVANCE FOR YOUR SUPPORT!

Leonardo